To the project manager, doing thing right means more than simply following some formula or methodology. It begins by being pragmatic and to respond appropriately to unexpected events. It also means recognizing when you are doing things wrong. For example, unless you are a Jedi Knight, getting the job done is not your job. For a project manager, providing the leadership that gets the job done by others is your job. If you find yourself completing tasks on the WBS – you’re not doing things right.

While knowing how to calculate a project’s ROI, develop a WBS, and derive the critical path are important skills, I don’t believe these and many other hard skills are critical success factors for the project manager. The title project manager contains the word “Manager”. To be a successful manger you first need to be a good leader and negotiator. I believe there are 4 areas where your leadership and negotiation skills are critical to running a successful project. They are:

- Managing project estimates

- Managing project communication

- Managing the knowledge community

- Managing the project constraints

Let’s look at each of these 4 areas and consider why they require leadership and negotiation and why they are considered critical success factors.

1. Managing project estimates

Estimating a task or milestone is not about applying a formula to average the results of a survey. Getting the opinion of a few colleagues does not provide a defendable estimate. It is about having the evidence to why you feel the estimate is reasonable and being in a position to negotiate any particular estimate. Estimates will also be negotiated and refined as your project progresses.

Invariably each time an estimate is put forth, someone will disagree with you. Generally senior management will challenge anything do to with cost and schedule – that’s their job. Without having a good defense and the ability to present and negotiate your position, your leadership skill will come under question and your project may be pushed into failure.

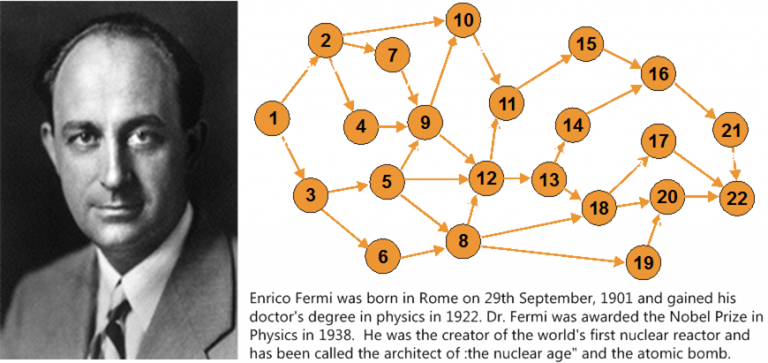

I have always liked the estimating approach taken by Enrico Fermi. It is especially good when it comes to negotiating and refining estimates as the project moves along and as more information becomes available.

Figure 1: Enrico Fermi

Fermi’s method for estimating is brilliant in its simplicity. But like all things that appear simple, the underlying work can be challenging. The process requires that you take a task or milestone and break it down into all its components and then make estimates for each based on assumptions. As Fermi would say, you need the courage to make assumptions. It’s the assumptions that then become open to dispute and negotiation – not the estimate itself. Fermi’s classic classroom example of this is his question to estimate how many piano tuners there are in Chicago. The estimate is based on a breakdown of assumptions. They are:

1. 9,000,000 people live in Chicago.

2. 2 people per household.

3. 1 household in 20 has a piano.

4. Pianos are tuned on average once per year.

5. Including travel time It takes about 2 hours to tune a piano

6. Each piano tuner works 8 hours a day, 5 days a week 50 weeks a year.

The resulting estimate is about 225 piano tuners in Chicago. Should someone take exception to the estimate of 225 piano tuners in Chicago, you can now negotiate and come to some agreement on the assumptions. When the project progresses and more factual information about the assumptions surface, the estimate can be adjusted.

A more famous example of this technique is the Drake Equation which is used to estimate the number of active and communicative extraterrestrial civilizations in our galaxy. A more pertinent example might be an estimate to hire someone required to fill a new job position needed for the project. The assumptions used might be:

- Develop Position Description

- Develop Recruitment Plan

- Select Search Committee

- Post Position and Implement Recruitment Plan

- Allowance for response

- Review Applicants (20 applicants)

- Develop Short List (4 candidates)

- Conduct Interviews (4 candidates)

- Select Hire (1 second interview)

- Conduct on-boarding process

What are your schedule and cost assumptions for each of these?

How many calendar days with this process take?

For more detailed information on project estimating see the article on Project Elaboration.

Occasionally an estimate will be unacceptable and the task must be done cheaper or faster. In those cases it’s time to negotiate the trade-offs between performance (quality), cost, and schedule. More on managing trade-offs is discussed later in the section managing the project constraints.

2. Managing project communication

For communication to take place it has to be formulated, delivered, received, and understood. Several barriers stand in the way of that process. To me, the first challenge for the project manager is what we call comprehensive listening. This involves both the listener and the communicator. First, the listener needs an appropriate vocabulary and language skill. For the communicator, complicated language or technical jargon will obscure the message. The message can be further blurred having several people hear and understand the message in different ways. The message may have been formulated, delivered, and received, but not understood.

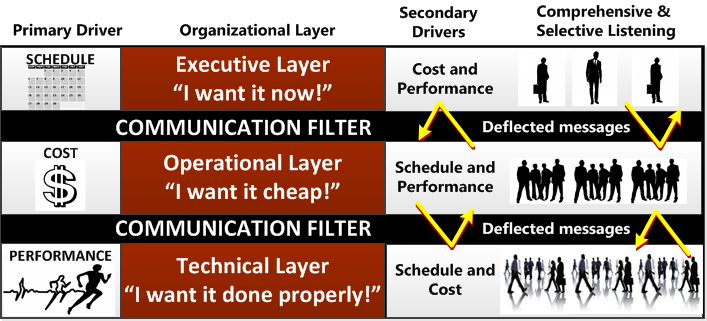

The second challenge is what we call selective listening. People don’t always listen or they will apply a filter that allows them to only hear what they want to hear. Selective listening can be avoided by understanding motivational drivers throughout the various layers of the organization.

Applying the concepts found in the article Constraint Reporting, we commonly find different motivational drivers between the executive, operational, and technical layers of the organization. See figure 2.

Figure 2: Communication bariers

Armed with this knowledge, project managers should be able to formulate their messages using appropriate language and media. In addition, they should be able to assure that key points are delivered and understood.

For help with overcoming these communication barriers and crafting the communication needed for your project please review the Project Communication Plan template.

3. Managing the knowledge community

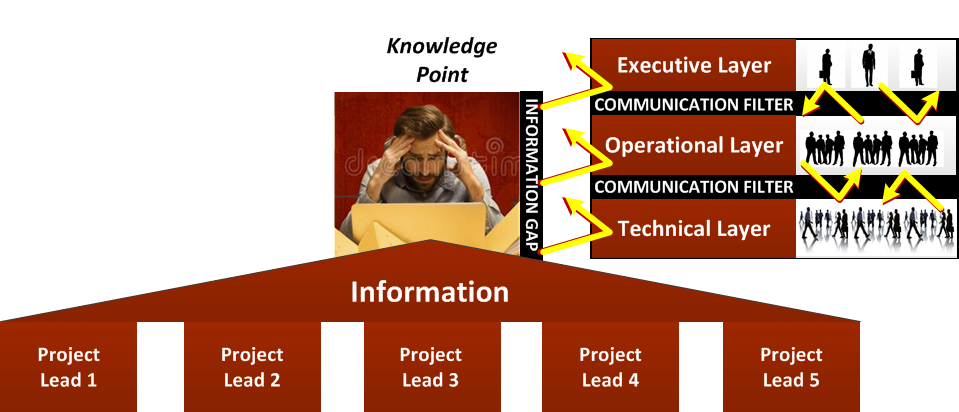

Information pouring in from your project leads can become overwhelming. All too often you become the single knowledge point for project communication. When that happens you may not be able to:

- Integrate information

- Provide sound advice to key decision makers

- Negotiate constraints from a position of strength

In almost every project there are two knowledge communities – the management group who initiate and sponsor projects and the project leads who deliver project artifacts. Integrating information coming from project leads is often a daunting task and a potential project failure point.

Figure 3: Unclear or confusing messages will be deflected

Your information and arguments may be defected because you were not able to defend your position with convincing details. Your position may be compounded by comprehensive and selective listening barriers. The consequence is that you may lose your leadership status with a good chance that your project is out of control and headed south.

The Jedi Knight

A multi-national organization wanted to centralize their help-desk operations. They had several help-desk units operating in various countries. Work duplication and communications was thought to be much higher than necessary. Additionally, each unit was applying their own standards and service-levels. The concepts of Globalization was a driving force for centralization.

The original project manager organized his team around 5 regional project leads – 1 from each country operating help-desks. Requirement information was pouring in from 5 different countries each claiming “unique” requisites to satisfy cultural or historical demands. National pride and ego also seemed to play a role in competing for leadership. Language and standards also played a role in communicating clear statements and diagrams.

The project manager thought he could coordinate and interpret the requirements and lead everyone to a common development target. See figure 3. The result was that the project manager could not defend a global application that satisfied managements vision of an effective and efficient operation. Management pushed back on proposals and the regions pushed back on demands. The resulting rebellion left the project manager unemployed and the project stalled.

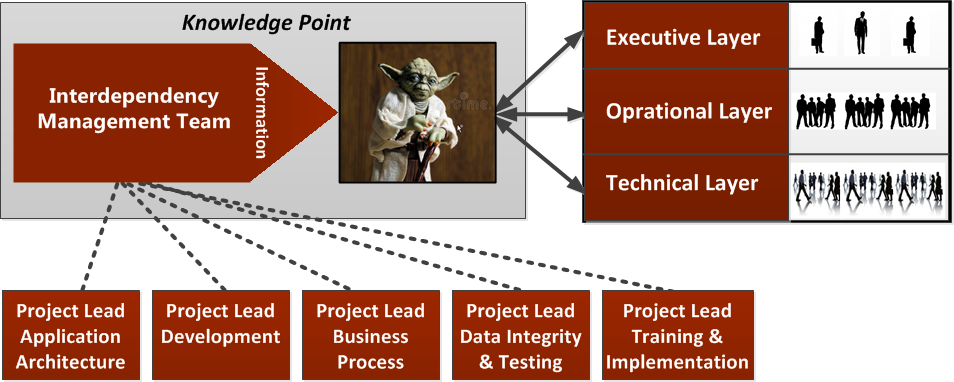

A new project manager was brought in and realized that mediating disputes fueled by national pride, ego, and language was too much even for a Jedi Knight. The current project organization, with a single point of knowledge, is always dangerous and, in this case, impossible. The knowledge point had to be expanded – but how?

His strategy was to group technical skill across boarders to form functionally based teams rather than regionally based teams. Then create an interdependency management team using the new project leads from each of the functional based teams. See figure 4. The new interdependency management team would form the core of the knowledge base which he hoped would assist with proposals, options, arguments founded on fact based logic, and negotiating points. He also hoped the new functional based organization would produce the following results.

- Mutual respect among colleagues with like skills and backgrounds

- Disuse of the the phrase “well, that’s not how we do it in ...”

- The adoption of ISO standards

- A multi-national sense of pride for the product

Figure 4: Clear fact based messages will be unarguable

The results were as planned. After approving a new project plan, with revised budgets, schedules, and clear defined project constraints, the project was successfully delivered on time and within budget.

While this was a relatively large project, the same results can be seen in many smaller projects. Bringing the team leads together formally with a clear mandate is key to establishing factual information and making the right choices.

4. Managing the project constraints

To successfully manage project constraints they must first be established. Some would call this setting the project’s rules of engagement.

Rules of engagement are a blend of MANAGEMENT and EFFORT elements that help establish and maintain unmistakable objectives for a project. These elements can be depicted an a matrix to plainly display and communicate the rules of engagement for a given project.

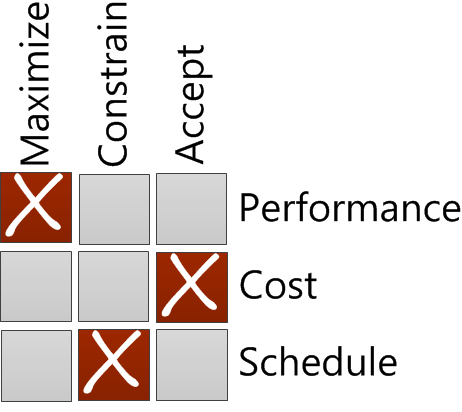

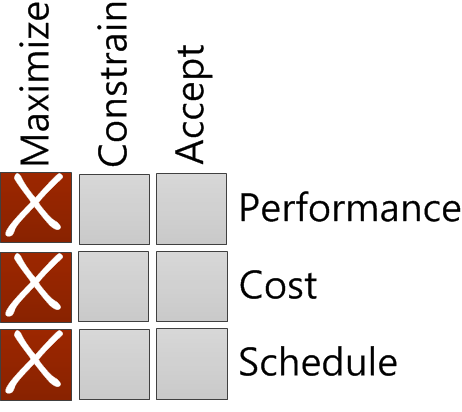

The effort elements are performance, cost, and schedule. Performance includes all the functions and features of the product or service being developed. Cost includes the financial resources budgeted to achieve the specified performance level of the product or service. Schedule is the time it takes to achieve the specified performance level of the product or service.

The management elements are maximize, constrain, and accept. These elements specify how each effort elements is treated during the project. Maximize means that the effort element cannot be negotiated or adjusted. Failure to achieve the maximized effort element would result in project failure. Constrain means the effort element can be negotiated to a degree, allowing for some flexibility without adversely affecting the project result. Accept means the effort element is accepted to achieve the specifications of the other two effort elements.

Figure 5: Apollo program rules of engagement

Displaying the relationship of constraints is best shown on a 3 X 3 matrix. See figure 5. The objective is to assign one effort element to one management element. When the project’s objective is properly articulated, the rules of engagement should be derived from the objective statement. For example, consider President Kennedy’s Apollo program objective. “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.”

This objective can be interpreted as “…returning him safely to the earth…” = maximized performance. Not returning him would result in project failure. “…before this decade is out…” = constrained schedule. No specific date was set – only that the project should be completed by the end of the decade. “…commit itself…”. There is no specific mention of cost in this phrase but the term “commit” can be inferred as “whatever the cost”. It can therefore be assumed that the project has an unlimited budget. See figure 5. These rules of engagement were maintained from 1961 through 1969.

Figure 6: Common rules of engagement

If the rules of engagement are not derived from the project’s objective you will likely not be able to defend changes in any of the elements. Without senior management’s agreement on a clear and properly articulated objective, I would bet your project is experiencing one or more of the following situations.

1. Scope creep. The performance requirements are growing without cost and schedule changes.

2. Budgets have been cut. But no change to schedule or performance has been approved.

3. Schedule has been maximized. You started with great performance expectations but are now pressured into maintaining schedule.

After a short time your project’s rules of engagement is likely attempting to maximize all three effort elements. See figure 6. In that case – you will fail.

For more detailed information and case studies on the rules of engagement, see the article on constraint reporting.

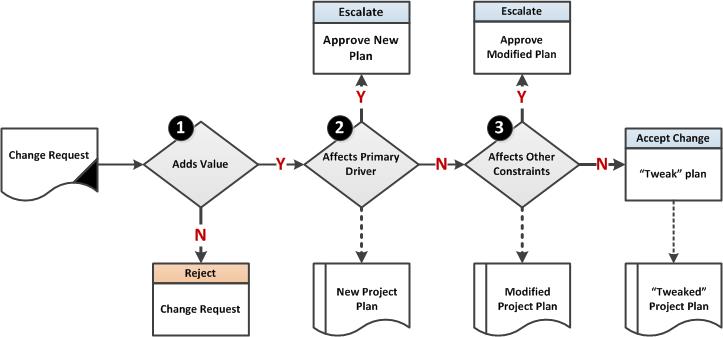

So how can we protect the alignment of these elements and minimize the need to negotiate trade-offs or worse – realignment? The answer is having a formal and effective change control process.

Regardless of how well initial requirements are stated, requests for change can be expected over the course of a project. It’s how we handle these requests that can make the difference between success and failure. It’s not so much about preventing scope expansion – that will happen. It’s about maintaining a common expectation of outcomes. That job falls to the interdependency management team.

Change management doesn’t simply assure that all change requests are integrated into the plan. Instead, it validates the value of the request, and assures that changes to the effort and management elements are properly argued and justified and that changes to the project plan accurately reflect changes to the performance, cost, and schedule expectations. See figure 7. When change requests come from higher management negotiations can become more intense requiring more fact based information.

Figure 7: Change Control Process

In summary, having the ability to develop and update estimates and a knowledge community that can assist with communication and manage project constraints may make the difference between finding new employment or emerging as project management’s Jedi Knight.