The world of project management is filled with support tools, certifications, methodologies, and talented project managers. Why then is the failure rate of projects at almost 70%.

An organization’s strategic plan is achieved through the execution of a series of projects. According to the Standish Group, the failure rate of project execution is around 68%.

Unfortunately, statistics for the failure rate of strategy execution are far from consistent. They range from 50 to 90% but there can be little doubt that the two statistics are related. At first it would seem obvious that if we could reduce the failure rate of project execution, we would increase the success rate of strategy execution. However, it is very possible to have successful projects and a failed strategy. This can happen when the organization is working on the wrong projects or has an impossible strategy – or both.

When we look at published reasons for project failure we see things like

- Leadership and governance issues

- Stakeholder engagement issues

- Team issues

- Requirements Issues

- Estimating issues

- Etc.

The list goes on. In fact, there is a web site listing 101 reasons projects fail. However, depending upon who is responding to the survey, many could be little more than excuses and not related to root cause.

Insight into what may be a root cause as to why many projects fail to deliver the strategic results hoped for can be gained by examining what appears to be two inescapable competing forces that contribute to project failure. These forces represent two distinct states: the project, a temporary state, and the organization, a permanent state. There is an intrinsic conflict between the two states. If left unrecognized and unattended, interaction between these two forces can produce catastrophic results.

This report begins with an understanding of these competing forces and provides a simple reporting process that can neutralize these forces and improve the success rate of project and strategy execution.

The Project and the Organization

Project Forces

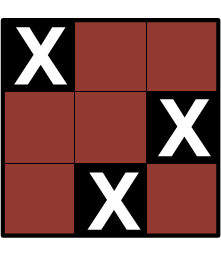

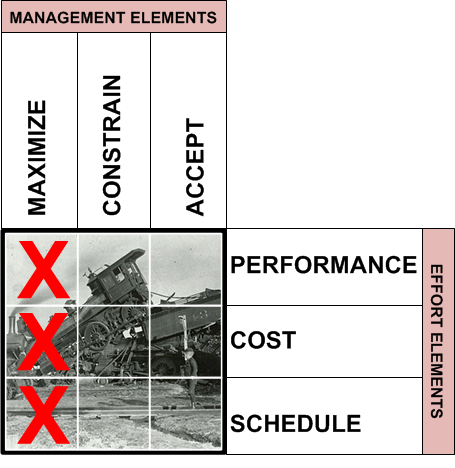

The dynamics of a project are controlled by what we will call the Rules of Engagement. It is the rules of engagement that are used as a foundation for project planning and decision making throughout the project. Rules of engagement are a blend of MANAGEMENT and EFFORT elements that help establish and maintain unmistakable objectives for a project. These elements can be aligned to a matrix to plainly display and communicate the rules of engagement for a given project.

The effort elements are performance, cost, and schedule. Performance includes all the functions and features of the product or service being developed. An example might be a system than can process “X” number of transactions per second or a product that must weigh less than four ounces. Cost includes the financial resources budgeted to achieve the specified performance level of the product or service. Schedule is the time it takes to achieve the specified performance level of the product or service.

The management elements are maximize, constrain, and accept. These elements specify how each effort elements is treated during the project. Maximize means that the effort element cannot be negotiated or adjusted. Failure to achieve the maximized effort element would result in project failure. Constrain means the effort element can be negotiated, allowing for some flexibility without adversely affecting the project result. Accept means the effort element is accepted to achieve the specifications of the other two effort elements.

Figure 1: Management elements matrix

To complete the matrix, simply align one effort elements to one management element. An example is maximized performance, constrained schedule, and accepted cost as shown in figure 1.

Once an effort element is aligned to a management element, it cannot be reused. For example, if schedule is maximized, neither cost nor performance can be maximized. Doing so creates an impossible situation. Simply stated, no one row or column can contain more than one “X”.

Once the alignment is complete, the rules of engagement have been identified and detailed project plans can now be developed. The same project under various rules of engagement will result in very different plans. It would not be terribly uncommon for the nature of the project to change after a project is well underway which would result in a change to the rules of engagement.

For example, a project may start with performance maximized, schedule constrained, and cost accepted. During the life of the project, funding may be severely curtailed, resulting in cost becoming maximized. Once an alignment changes one or both of the other alignments must also change. For example, performance may now become constrained and schedule may become accepted.

Organizational Forces

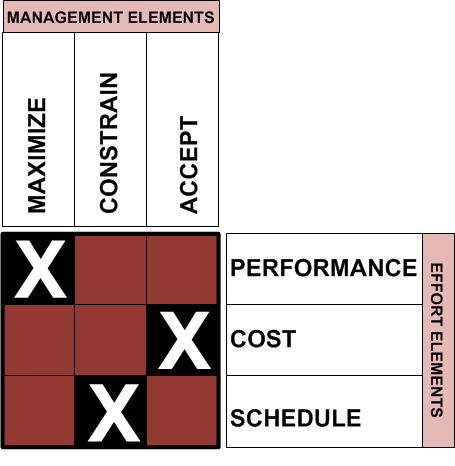

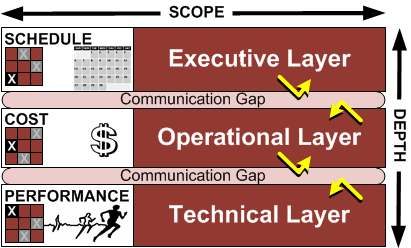

Figure 2 represents a model of almost any organization. It could be a university, a pharmaceutical company, and manufacturing company, a governmental agency, a hospital, or a department store.

The organizational scope spreads across the top of the model representing the functions of an organization, such as manufacturing, accounting, information services, customer services, inventory, research, and development. Depth lines the side of the model showing the increasing level of detailed activity within each function of the organization.

Figure 2: Organizational layers

The Executive Layer

Senior executives know a lot about their organization, its activities, and its functions. However, they may not know a great deal about the details of how each area operates. For example, a vice-president of information services understands why the department exists and what its mission and objectives are, but may not know all the details about the operation of particular tools and technologies deployed by their department.

The Operational Layer

Middle-level managers understand what their functional areas do and what it takes to get the job done. For example, a software development manager would know requirements and the process behind the deployment and use of a technology or application. They would also be able to question the estimates around performance, cost and schedule. However, they would not be expected to be proficient in actually developing the software for a required application.

The Technical Layer

An organization’s technical layer is the largest group, made up of non-management workers, technicians, and skilled and non-skilled labor. These people are responsible for knowing how to perform specific project related tasks, such as software development, documentation writing, machine operation, and training.

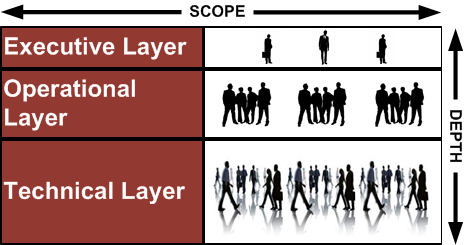

Motivational Drivers

Each organizational layer has a motivational driver that influences day-to-day decisions: performance, cost, or schedule. While all three motivational drivers influence all layers, typically one driver is the primary influence of a specific layer. See figure 3.

Figure 3: Motivational drivers by layer

Schedule, as a motivational driver, causes an individual or group to place the highest priority on meeting milestones. The influence of this driver is typically most dominant in the executive layer. For example, We have seen executives announce delivery dates before their project managers have developed plans to produce the product. In one particular case, the executive layer committed to both a price and delivery date before engineering could provide a proof of concept for the product – it happens.

Cost, as a motivational driver, causes an individual or group to place the highest priority on meeting budgets or reducing cost. The influence of this driver is typically most dominant in the operational layer. Middle management faces the constant challenge of controlling costs by whatever means, including downsizing, reorganizing, and generally attempting to do more with less. For example, revenue projections are often not met forcing middle management to reassess priorities and reduce operating or capital budgets.

Performance, as a motivational driver, causes an individual or group to place the highest priority producing the best possible product quality. The influence of this driver is typically most dominant in the technical layer. These people are responsible for producing the final product. They may have spent years perfecting their trade and they will want to ensure the product is a reflection of their skill and talent.

Communication Gaps

Motivational drivers influence more than just decision making. They influence entire behavioral patterns that can create intrinsic obstacles for the organization. The most common obstacle between all layers of the organization is poor communication.

Figure 4: Motivational drivers with communication gaps

Because people listen selectively and filter, the fidelity of the communication spanning the organizational layers is questionable resulting in distinguishable communication gaps. An executive, for example, may be highly responsive to schedule information, and less responsive to cost or performance information. A corresponding result is played out within each layer. See figure 4.

Because of these gaps, the project is allowed to continue with people in each layer perceiving that the project is progressing satisfactorily according to their interpretation of the rules of engagement. In reality, however, the project may be completely out of control. It is interesting to note that Ineffective communication will almost always result in control defaulting to the technical layer. Management may continue to control actions but is no longer able to control results.

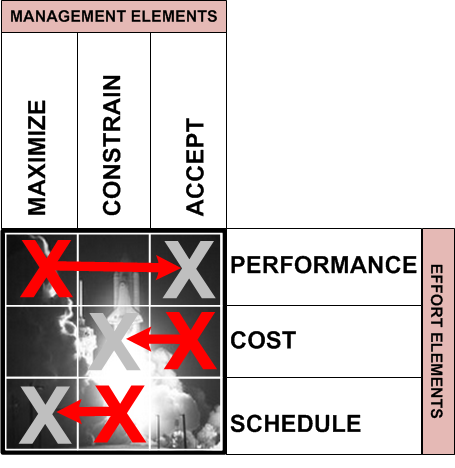

Figure 5: All motivational drivers are maximized

Once communication lines break down management processes are no longer effective. Independent actions, taken within each of the organizational layers, are done so to accommodate their primary motivational drivers. See figure 5. Ultimately, the project will fail with little to no advance warning.

Case Study

The Apollo Program

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy announced a bold initiative to end men to the moon. “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.”

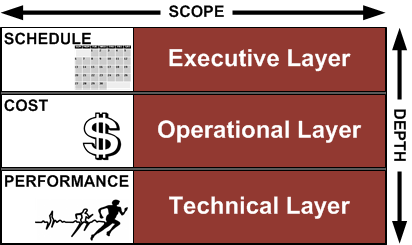

Figure 6: Apollo project rules of engagement

Consider how the goal established the rules of engagement. Kennedy’s statement contains two effort elements: performance and schedule. The performance statement is “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” The key here is “returning him safely to the earth.” If the astronaut could not be returned safely, the project would be cancelled. Based on this statement, the performance of the project would be maximized.

“Before this decade is out” is a clear schedule statement indicating that the schedule was somewhat flexible. The political reality of this statement was to beat the Soviet Union to the moon. The United States could afford to be a little late without jeopardizing the success of the project. The schedule was constrained.

President Kennedy could not make a clear cost statement because the budget was in the control of Congress. Kennedy relied on popular support to pressure Congress to fund the project as specified, which they did, accepting cost.

In July of 1969, the Eagle lunar module landed on the moon with Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin aboard. Three days later returned safely to the earth. See Figure 6.

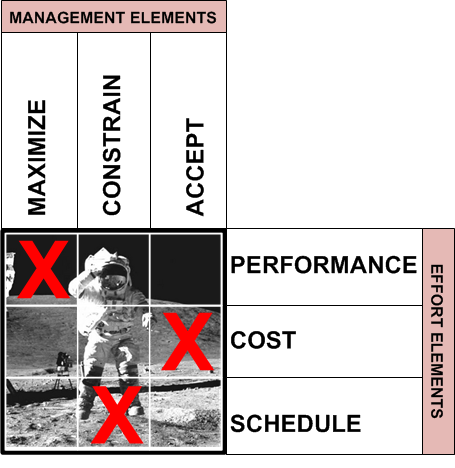

The Shuttle Program

NASA began the shuttle program with the same rules of engagement. However, through the late seventies and eighties, Congress was not so disposed to accept the cost and began to put limits on NASA’s budget, constraining cost.

Once an effort element is aligned with a management element, it cannot be reused. Because schedule had previously been constrained, it should have been moved to accept when cost became constrained.

In order to regain the original levels of funding, NASA began to compensate by allowing influences to affect operations and decision making: attracting private sector funds through the satellite launching business; regaining both public and congressional confidence; and attempting to return to the “good old” glory days.

To satisfy these motivational factors, NASA needed to establish its credibility from both a political and business perspective – something it had never done before. The most visible way of establishing this kind of credibility was to maintain schedule. The year 1985 brought an aggressive schedule to the shuttle program. Launches were regular and on time. Schedule had become maximized.

Figure 7: Shuttle program hidden ruels of engagement

NASA began to shift its rules of engagement without reassessing the entire program. By maximizing schedule, rather than accepting schedule, NASA maximized both performance and schedule – creating an impossible situation. The moment NASA decided to maximize schedule, and possibly without fully understanding what they had done, they allowed performance to be accepted. See figure 7.

On January 28, 1986, with ice on the launch pad, a decision was made to launch Challenger and its seven crew members – on schedule. A few seconds later the craft exploded.

Although the rules of engagement had changed, NASA allowed organizational pressure to influence project decisions. This organizational influence widened the communication gap between the organizational layers allowing motivational drivers to take control over actions with disastrous results.

Reporting

Using the rules of engagement to report status at all levels in the organization is critical to communicating and agreeing on problems and solutions. All projects can have unforeseen issues arise that can result in tweaking or rewriting current plans. When this happens decisions must be made to determine appropriate actions. Decision making in regard to these plans must be influenced by the project’s rules of engagement.

The actions taken arising from unforeseen issues must be in-line with the criticality shown by the rules of engagement. For example, if schedule is accepted and the project status reports a slippage in schedule, limited action might be taken to correct the problem thereby reducing a potential strain on cost and performance. However, if schedule is maximized and the project reports a slippage in schedule, more dramatic action may be taken to correct the problem to the detriment of cost and performance.

Knowing how problems encountered during the execution of a project are impacting the rules of engagement is critical to determining an effective and reasonable response.

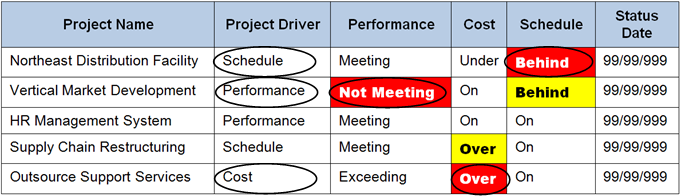

Figure 8: Constraint reporting

I am aware of two strategy implementation products that contain project status reporting mechanisms that require this type of reporting. See figure 8. Notice that the color coding on the report indicates how the rules of engagement effort element compare against the maximized management element. After the values are selected for the effort elements, the application compares the effort reporting to the maximized management element (the project driver). If a problem with an effort element is aligned with the maximized management element, the report color codes that entry in red. If a problem with an effort element is not aligned with the maximized management element, the report color codes that entry in yellow. If no problem exists with the effort element, then no color is applied.

High-level constraint reporting can provide several benefits for all stakeholders, including:

- An opportunity to re-examine the project’s strategic value and decide whether to continue with the project or not.

- An opportunity to realign the rules of engagement.

- An opportunity to remedy project resources.

- An opportunity to redress project requirements to compensate for current project realities.

- An opportunity to focus investigations on key project issues.

- Provide status reporting transparency to all stakeholders